OBITUARY

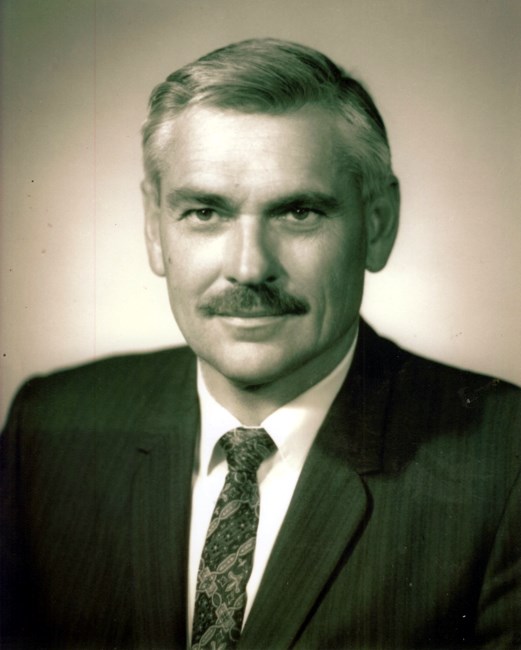

Ralph A. Nobles

May 29, 1920 – February 20, 2015

Ralph Nobles, a nuclear physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project, personally witnessed the first nuclear bomb blast in the New Mexico desert, and later led efforts to save thousands of acres of San Francisco Bay wetlands from development, has died.

"Ralph always had a big smile. He was very handsome, like Clark Gable. But he did give a damn," said Florence La Riviere, a longtime Palo Alto environmentalist, recalling a former national wildlife refuge manager's quip about him.

A Redwood City resident for half a century, Nobles died Friday following complications of pneumonia at Kaiser Hospital in Redwood City. He was 94 years old.

Born on a farm in Dexter, Missouri, in 1920, Nobles was a standout student who would eventually earn a Ph.D. in physics. At the suggestion of a physics teacher, he volunteered on the Manhattan Project, and with his brother, William, was chosen. The two moved to Los Alamos, New Mexico, where Robert Oppenheimer and other leading scientists of the 20th century built the world's first atomic bomb in concert with Enrico Fermi, Edward Teller and other researchers.

In an article for the December 2008 newsletter of the Los Alamos Historical Society, Nobles vividly remembered standing in the desert on July 16, 1945, at the Trinity Test Site, south of Albuquerque, in a bomb shelter to observe the blast 5 miles from ground zero.

"From the standout point of sheer drama, tension and excitement, nothing else in my life has equaled, or even come close to that night at Trinity," he wrote, "when, for better or for worse, we let the nuclear weapons 'genie' out of its bottle and initiated a chain of events that precipitated an abrupt ending of World War II."

Nobles' job was to operate data recorders with eight other scientists in the shelter. When he was the equipment working, the 25 year old walked outside and watched the blast through a light shield.

"It was an awesome sight, the likes of which had never been seen before," he recalled. "There was a brilliant, seething, white hot ball of rapidly expanding light, now maybe 10 or 20 times the apparent diameter of the sun."

As he watched the mushroom cloud grow, Nobles was knocked to the ground by the shockwave.

"It sounded like the world's loudest clap of thunder-thunder that echoed back and forth between the surrounding mountain ranges,:" he wrote. Minutes later, Nobles and his co-workers sped away in trucks, escaping significant radioactive exposure.

Nobles lived in Los Alamos for more than a decade afterward, and in 1954, married Carolyn Fisher, an Ohio native who had been working as a secretary on the project. The pair adopted two daughters and moved to the Bay Area.

From the early 1960's until the 1990's, Nobles worked at the Palo Alto research laboratories of Lockheed Missiles and Space. He served as chairman of the Redwood City Planning Commission and was heavily involved in issues from civil rights to preserving the environment.

An avid sailor, Nobles became concerned about the relentless filling and diking of San Francisco Bay. In 1962, while sailing, he was constructions crews working for developer Jack Foster pouring rock and dirt into bayfront wetlands.

"I just felt sick in my heart," he told this newspaper in a 2008 interview. "They went out with their dredges to San Bruno Shoal and piled up millions and millions of tons. They changes the whole hydraulics of the bay."

Lost were vast amounts of habitat for ducks, fish, harbor seals and other wildlife. Born was Foster City, a city of 30,000 people.

In 1981, Mobil Oil won approval from Redwood City to build "South Shores," a mix of 4,700 homes, offices and a hotel on Bair Island, a 3,000-acre wetland area just north of the port of Redwood City. Nobles, his wife and their allies formed "Friends of Redwood City," collected signatures, and put the project on the ballot, where it was devasted by 47 votes.

When a Japanese developer came back in the 1990s with a similar plan, Nobles and other environmentalists fought it, and the nonprofit Peninsula Open Space Trust bought Bair Island in 1997 for $15 million. Today it is part of a national wildlife refuge.

In 2004, Nobles similarly led a fight to block plans by another developer to build a $1 billion complex of 17 condominium toers next to the property. Redwood City voters rejected it, too.

"The main reason we like to live in the Bay Area is the bay," he said. "That's what makes it a special place. The wetlands are at the base of the food chain. They are the lungs of the bay. Without them, the bay would become basically a cesspool."

For decades, Nobles was one of a small number of activists who write letters, attend meetings and do often tedious work to preserve the bay, usually with little public awareness.

"I think he'd like to be remembered as a devoted husband and a loving father, but also as somebody who participated in life," said Nobles' daughter, Elizabeth Nobles Cozart of Redwood City. "He traveled all over the world. He fought for the environment and for people, and he helped the country win World War II. He touched so many lives."

Nobles is survived by his brother, William Nobles, of Rio Rancho, New Mexico; his daughters, Elizabeth Nobles Cozart of Redwood City, and Sarah Turck of Lodi, along with grandsons Benjamin Turck, Daniel Cozart and Scott Cozart, and one great-grandson, Sawyer Cozart. A public memorial service is planned for 11 a.m. March 21 at Redwood Chapel, 847 Woodside Road in Redwood City. Donations can be made to Save the Bay or the Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge.

By Paul Rogers covers resources and environmental issues. Contact him at 408-920-5045.

Show your support

Add a Memory

Share Obituary

Get Reminders

Past Services

Memorial Service

SHARE OBITUARYSHARE

- GET REMINDERS

v.1.13.0