OBITUARY

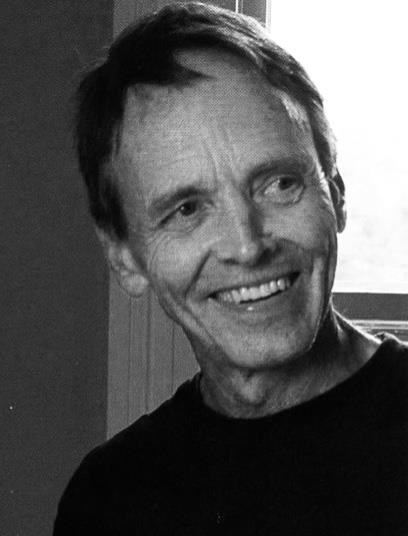

Michael John Simon

December 27, 1947 – August 29, 2021

Born in Springfield, Minnesota on December 27, 1947, he was the son of the late, Rudolph George Simon and Lola Mae Larsen.

Survivors include his wife, Susan Roberts; his brothers Jim Victor Kretsch, Donald Ervin Kretsch, Tom Steven Simon; his nieces Linda Kretsch, Sandy Kretsch and Deb Melby; many more nieces and nephews and sixty-one cousins. Sister-in-law Jane Roberts Robertson; two brothers-in-law, Frank Bryant Roberts, Jr. and John Edmond Robertson; nieces, Katherine Robertson Byrne, Julie Jelliffe Robertson and nephews John Andrew Robertson, Robert Roy Byrne; great nephews, Nicholas Edward Byrne, John William Byrne, John Logan Robertson and great niece, Reese Patricia Robertson.

Condolences on our website BersnteinFuneralHome.com

In Lieu of flowers, please support: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 89 Haystack School Drive, Deer Isle ME, 04627

Michael grew up in a farming community and was the first person in his immediate family to go to college. The head of the ceramics department at the time was nationally acclaimed potter Warren MacKenzie, who became a father figure and mentor to many of his pupils. When Simon recalls his time in the studio at the University of Minnesota, it is evident that MacKenzie was one of the most influential characters in his life: “Warren opened the door; he led all of us to believe that pottery could be really an expressive form, a place where you could have the reward of being able to put forth your feeling. That was the beauty of Warren’s teaching: the feeling of his dedication and how much he saw in the pots. He has ultimate confidence that the pots could carry his total self, and that was what we saw.”

After graduating from Minnesota in 1970, Simon moved to Georgia to join former classmate Jerry Chappelle, who had taken a position in the University of Georgia’s ceramics department, founded in 1941 under the direction of Earl McCutchen as the first ceramics department in the Southeast. Simon’s work evolved as he practiced and grew into his own voice. “With every kiln load, or a good day’s throwing, you would learn something. We started from such a basic level, and we had that first bit of time.”

In the late 1970s, Simon’s fellow potter, Ron Meyers, who taught ceramics at UGA, encouraged him to enroll in graduate school. He won a Ford fellowship and was offered an opportunity to teach, and graduated in 1981 with a master’s degree in ceramics from Georgia. During the 1980’s, Simon built and fired his first salt kiln after visiting Mark Pharis, a former classmate, in Minnesota. The salting produces a varying surface due to the heat of the kiln. Simon says, “the clay had all the character, and I could just leave it alone and let the kiln work on it… It changed my attitude about the pots, somehow. It took about twelve years to become a potter. In the 80s I felt a lot more like a potter and started to like my pots more. A lot of it is just a matter of time and experience doing the work.”

In his book, Michael Simon: Evolution, Simon illustrates the development of his work. He and his editor and wife Susan Roberts, professor of art at UGA, write about the forms Simon holds dear: cups, bowls, jars, vases, pitchers and teapots. In acknowledgement Simon says, “No one has meant more than my wife Susan. From the beginning she has invested her complete self, taking me seriously in my passage to make good pots and then helping me write about it. I was always reaching out, she was always catching. This work would not exist without her. I cannot say enough.”

Simon writes, “Pots from those early years held clues to how the work developed, and I began to forget the details,” he says. “Remembering the development seemed crucial to helping move the work forward. I decided then to keep a pot from every kiln load and to choose it before any left the studio. In some firings, one pot would simply declare itself. Other picks represent the attainment of a desired form, an example of glazed surface or a breakthrough in motif. These picks serve as markers of my development, lest I forget where I started.”

Simon describes the process of change as proceeding “slowly and subtly, but the growth carries on and is most satisfying. The real significance of years of potting can be found in the way one pot leads to the next. Slow progress comes into view in the development of the work in total, not in the beauty of any one pot. There is no end.” As Simon puts it, “Thought is fleeting and the real learning is in the making.”

Simon’s body of work is made up of functional objects. The basis of his work originates from the utilitarian role that pots play within the household as vessels for food preparation, serving and storage. He says, “I believe that if the work is sound, my audience will be moved to understand the expression available in the handmade pot.”

Phillip Rawson’s essay, “The Value of Craft” considers the connection between craft and fine art. “Simon’s pottery operates on both levels, resulting in objects that have a utilitarian purpose but are elevated to fine art because of their beauty and significance. His objects add value to the lives of their users and provide the opportunity to behold the exceptional integration of purpose and mind expressed by his hands in the damp clay.” Simon’s work, life, and artistic philosophy have made an impression on many students and will continue to influence those who encounter his work in the future.

Friends, Potters, Artists speak:

Michael was beloved of so many of us who were touched by his creative genius and passion for pots. His uncompromising clarity- the hardness that that takes- was always counterbalanced by a warmth and generosity and modesty- something of the prairie in the artist whose work encompassed all the world and time. No doubt he changed the direction of studio pottery. I feel lucky to have encountered him. Mark Shapiro, studio potter

We first met Michael in 1978 when we three received Ford Foundation Artist in Residencies at UGA. David and Michael bonded as fellow ceramists and as friends. Michael’s work, his thoughtful nature, his wry sense of humor and his remarkable courage impacted both of our lives. Our dear friend and almost brother. Michael was an original. David Crane, Janet Niewald Crane

We had a long, treasured friendship. Michael was/is my favorite potter. He was all of my pottery friends’ favorite potter. His pots were his. No one else’s. That’s what we all respected about his work, and wished for in ours. I will miss Michael’s love. Craig Bryson

Michael was a great teacher at the right time. He gave me understanding that form was not silhouette, thinness was only thin, and one could throw with precision and still make a bad pot. Michael as a potter was able to merge form, decoration and utility in such a beautiful and considerate way. His pots resonate with a love of clay and process. Tool marks were clear and important, trimming was always called cutting, and the clay itself was showcased. We have lost a great potter, who changed American Clay through quiet clear thoughtful intention and presence. Simon Levin of Woodfire

Michael had such a refined and beautiful spirit…The world needs more of this, not less. We are all diminished with his passing. Scott Belville

Collections:

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, New York

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

Renwick Gallery, Washington, DC

Corsaw, Collection of Functional American Ceramics, New York State College of Ceramics, Alfred University, Alfred, New York

Los Angeles County Museum, Contemporary Ceramics Collection, Los Angeles

Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art, Mashiko, Japan

Minneapolis Museum of Arts, Minneapolis

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City Missouri

Racine Art Museum, Racine, Wisconsin

Weisman Museum, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

Education:

1980 MFA, The University of Georgia, Ceramics

1970 BA, University of Minnesota, Studio Art

Publication:

Michael Simon: Evolution, Univ. of North Carolina Press, Northern Clay Center, ed. by Susan Roberts, 112 color illus., ISBN 978-0-8078-7214-7, Cloth, 144 pp.

Show your support

Add a Memory

Share Obituary

Get Reminders

Services

SHARE OBITUARYSHARE

- GET REMINDERS

v.1.14.0