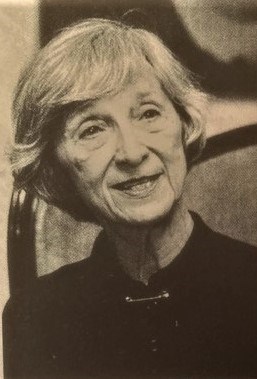

OBITUARY

Borka Tomljenovic

October 4, 1917 – April 28, 2021

103, died on April 28 after suffering a stroke in her Ann Arbor home and receiving hospice care for several days. Her life is noteworthy because family members loved her but also because of real interest coming from the way she moved among cultures approximately every quarter of a century.

EARLY YEARS (1917-1940)

Born on October 4, 1917 in Zenica, Bosnia to a Serbian Orthodox couple as World War I raged and October revolution in Russia gave birth to communism, she spent childhood in Tuzla absorbing the melting pot of Serbs, Croats, Muslims, Jews, gypsies and others that Bosnia had become, and was convinced that very different groups can and must live peaceably together. Her father was one of Bosnia's first surgeons trained in Vienna and an X-ray pioneer; she treasured this parent and copied his handwashing habits and life of discipline ingrained by education in a Jesuit Gymnasium in Zenica, her entire life. She remembered her varied school friends and in old age would recite the names of those alive and dead. Her first memoir, Bosnian Counterpoint, in 1997 at age 77 recounted stories and events from Bosnia during those early years. She amplified these memories and testimonials in Remembrances of Vanished Yugoslavia: Part 1 Bosnia 1917-1941 published by Amazon in 2015 when she was 98. Education was vital, and she completed gymnasium studies followed by a bachelor’s degree at Belgrade University in English language and literature. Borka married Juraj Tomljenović, a Croat, in 1938. Their daughter, Katarina, was born in Tuzla in 1940.

ZAGREB PERIOD (1940-1962)

As the threats of World War II increased, the young family left Bosnia for the Croatian capital Zagreb. In her second memoir in 1999 Neither on the Earth nor in the Sky, Borka now 82, recalled the hardships of war, occupation by the Nazis, start of communist regime, and the challenges of existence as a Serb in the face of Croatian nationalism. Borka cherished the cultural pleasures of Zagreb, a major European metropolis. In 1948, she accepted the position of lecturer in English at Zagreb University, taught classes, and joined a major project preparing a large Croatian-English dictionary initially published by Zora in 1950s and edited by Rudolf Filipović, a copy of which is in UM Graduate Library. The resulting volume was a big success, and 21 new editions were completed over the next forty years. On a personal level, Borka divorced her husband as her key objective became Katarina's education and future success. Despite Communist roadblocks, she found a way for Katarina to enter and complete a classical gymnasium program followed by two years in of biology study at Zagreb University. She started teaching Katarina English at age 6 and thus paved the way for her advanced studies at the University of Pennsylvania in 1961.

LIFE IN BELGRADE (1962-1992)

As her parents aged, left their Bosnian home and moved to the Yugoslav capital, Belgrade, Borka left Zagreb University and came to Belgrade to provide assistance. She continued to teach English classes part time but essentially served as caretaker for both parents as first her mother, and then her father, became ill and died. Belgrade was and is culturally very different from Zagreb and became a decidedly less happy experience. She experienced double-edged discrimination with her Serbian friends accusing her that she was a Croatian supporter, and her Croatian friends forsaking her for being a Serb and moving to Belgrade. After her father's death, Borka chose to remain in Belgrade with her newly widowed younger sister, Branka Šonda, whose husband Konstatin and his father built and operated a famous Šonda chocolate factory in Belgrade before WWII. Borka exchanged several visits with her daughter and three grandchildren in America. Branka's death in 1991 along with the sharp new conflicts as Yugoslavia split into several pieces hastened Borka's 1992 decision to herself become an American immigrant. She documented the disintegration of Yugoslavia in a travelogue Requiem for Yugoslavia in 1996 describing the trip she, her son in law, daughter, and grandson Richard took along Serbian Morava River dotted with Byzantine monasteries, across the mountains of Montenegro and along the Adriatic coast. In this book, Borka bears testimony to disintegration of communism which started the year of her birth, but also to disintegration of Yugoslavia which she mourned.

LIFE IN ANN ARBOR

Joining her Ann-Arbor-based daughter and new son-in-law at age 74, she began again to make a new life and accepted part time employment at UM's Center for International Students. Here the friendly administration of William Nolting and popularity with both US and foreign students provided major benefits. Several years later at 81, she became eligible for Social Security and Medicare benefits and finally retired. Her grandchildren gave her a white adult tricycle, and she spent fifteen years riding up and down South University Avenue as well as to the Farmers' Market. She loved fine art, classical music and Pushkin poetry which she often recited in Russian. Toward the end of her life, she lost her hearing but remained caring and generous to so many around her and contributed occasional short stories to Ann Arbor News.

All her family will miss her sorely: daughter Katarina Tomljenović Borer, son-in-law Paul Wenger, granddaughter Elizabeta Borer Meyer and husband Christopher Meyer, grandson Robert Chamberlain Borer III and wife Sherri Borer, grandson Richard Christopher Borer, great grandsons Nicholas Alexander Meyer and Robert Chamberlain Borer IV, along with great granddaughters Christina Maria Meyer, Zoe Alexandra Borer and Caroline Verona Borer. A memorial gathering for celebration of Borka’s life will be held on Saturday, May 15 at 11:00 a.m. at Muehlig Funeral Chapel in Ann Arbor at 403 South Fourth Avenue for family and close friends. Memorial gifts to a charity of the donor's choice are suggested.

Show your support

Add a Memory

Share Obituary

Get Updates

Services

SHARE OBITUARY

- RECEIVE UPDATES

v.1.8.18