OBITUARIO

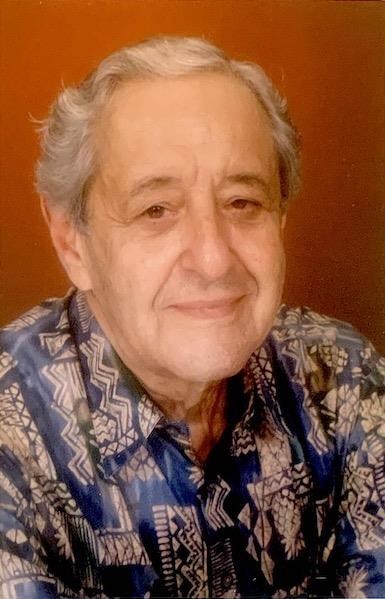

Dr. Mortimer Mishkin

13 diciembre, 1926 – 2 octubre, 2021

Mortimer Mishkin, a neuroscientist who received the National Medal of Science for his role in unlocking some of the most vexing mysteries of the brain, including how memories are made and kept, died Oct. 2 at his home in Bethesda, Md. He was 94.

His daughter Wendy Mishkin confirmed his death but did not cite a cause.

Dr. Mishkin spent more than six decades at the National Institutes of Health, where he served for years as chief of the Laboratory of Neuropsychology within the National Institute of Mental Health. He became renowned within his field for his findings related to perception, memory and the circuits that connect one part of the brain to another.

“Studying the brain is both horribly and wonderfully complicated,” Dr. Mishkin once remarked, reflecting on his career. “It’s so frustrating it takes such a long time to figure out even a few of the thousands of circuits, but every discovery is a fantastic high.”

Dr. Mishkin was credited with contributing to numerous such discoveries.

Betsy Murray, the current chief of NIMH’s Laboratory of Neuropsychology, said in an interview that before Dr. Mishkin, many neuroscientists were preoccupied with understanding the various structures of the brain, such as the hippocampus or the amygdala. Dr. Mishkin, she said, was an “early proponent” of the idea “that we had to understand the entire neural circuit.”

His research illuminated the differences between cognitive memory — which involves specific information, such as a phone number, and discrete events like a birthday party — and noncognitive memory, which forms the foundation of habits and skills like making a daily commute or playing a musical instrument. Cognitive processes, he argued, take place in the limbic lobe of the brain, whereas behavioral memory is centered in the basal ganglia.

Dr. Mishkin conducted extensive research on primates. By studying lesions on monkey brains, he and a colleague, Karl Pribram, helped demonstrate that the inferior temporal cortex, a part of the brain located far from the primary sensory area, figured in visual discrimination of objects. It was a “big moment,” Dr. Mishkin told a Dartmouth College alumni publication years later, because “the whole idea of circuitry became real.”

Dr. Mishkin’s career coincided with technological advances that allowed ever more sophisticated imaging of the brain. In addition to his findings on vision, his work was credited with expanding scientific understanding of the relationship between memory and sensory systems including hearing and touch, as well as conditions such as amnesia.

His National Medal of Science, awarded in 2010 by President Barack Obama, recognized “his contributions to understanding the neural basis of perception and memory.”

“There is no more complex piece of matter in the universe than the human brain, and so the complexity is a huge challenge,” Dr. Mishkin said at the time. “Each brain area is important for a different kind of behavioral or mental function, yet no area is an island. Every area is part of a circuit. So we’ve been identifying pathways and trying to figure out how they work.”

Mortimer Mishkin was born in Fitchburg, Mass., on Dec. 13, 1926. His mother worked in a family grocery store, and his father was an insurance agent for Metropolitan Life. Both parents were Jewish immigrants from Russia.

Dr. Mishkin left high school early to enter a Navy officer training program during World War II. The program took him to Dartmouth, where he received a bachelor’s degree in business management in 1946. After postwar Navy service in Japan, he studied psychology at McGill University in Montreal, where he received a master’s degree in 1949 and a PhD in 1951.

He was hired in 1955 at NIH and spent the rest of his career there, serving as chief of the section on cognitive neuroscience. He retired in 2016, at age 90, but returned the next year as a scientist emeritus.

Dr. Mishkin’s marriage to Patricia Sheppard ended in divorce.

Survivors include his wife of 50 years, Barbara Friedman Mishkin of Bethesda; two daughters from his first marriage, Wendy Mishkin of Bethesda and Susie Wheatley of Pequea, Pa.; two stepdaughters from his first marriage, Roberta Zimnowodzki of Placentia, Newfoundland, and Patricia Hoovler of Fredericksburg, Va.; four stepchildren from his second marriage, Diane Thaler and Amy Thaler, both of Bethesda, Paul Thaler of Washington and David Thaler of Boston; a sister; nine grandchildren; nine great-grandchildren; and nine great-great grandchildren.

Dr. Mishkin’s honors included induction into the National Academy of Sciences in 1984 and the National Academy of Medicine six years later.

“As we’re able to learn more about how the brain works and how to fix it, millions of people are going to benefit,” he said when he received the National Medal of Science, “and through that process understanding will develop about the role of science in having made all of that possible.”

-Published in the Washington Post

Please consider a donation in lieu of flowers to the Brenda Milner foundation for the study of memory dysfunction. Donations can be made in Mort’s name to the Montreal Neurological Institute-Hospital at https://www.alumni.mcgill.ca/give/index.php?new=1&new=1&formtype=MNI

or contact

[email protected] or call (514) 398-1958

The philanthropy office will ensure the funds go to support the purpose of Dr. Milner’s foundation.

Muestre su apoyo

Comparta Un Recuerdo

Comparta

Un Obituario

Obtenga actualizaciones

Servicios

COMPARTA UN OBITUARIO

- RECIBE ACTUALIZACIONES

v.1.8.18