OBITUARY

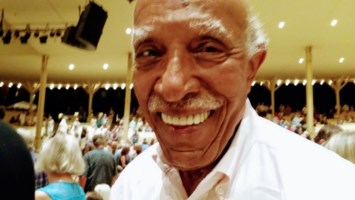

Merrill Pittman Cooper

9 February, 1921 – 8 May, 2023

City, New Jersey on May 8, 2023 at the age of 102.

Beloved by family and friends, Cooper was a gifted orator, avid baseball fan, jazz music lover and skilled political analyst. He will be remembered for his class, wit, grace and brilliance.

Born on February 9, 1921 in Kearneysville, West Virginia (near Charles Town) Cooper attended public school until the eighth grade, at which point the state no longer provided public education for African

American students. Cooper’s mother worked hard to pay for his enrollment at the historically significant Storer Normal School in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, which was established in 1867 to initially educate

formerly enslaved children and counted Frederick Douglass as a trustee. The Niagara Movement (a precursor to the NAACP) held its first conference on American soil at Storer in 1906 where W.E.B. Du Bois spoke about the demands of African Americans for voting rights, educational and economic opportunities, justice in the courts, recognition in unions and the military. Cooper was also influenced

and taught at Storer by leading scholars of the time, including Dr. Madison Spencer Briscoe and Waters Edward Turpin - who would later make history in parasitology and literature, respectively. Cooper commuted daily to Storer until 1938 when the family could no longer pay tuition and he withdrew his senior year. Remarkably, his high school diploma was later personally conferred by the Jefferson County, WV Superintendent on March 19, 2022 (pre-dated effective May 1938) through the efforts of his son-in-law, Rodney Beckerink.

Near the end of 1938, Cooper followed his mother to Philadelphia, PA seeking employment. After working several temporary jobs, he was hired among the first African American trolley car conductors

in 1945. He started six months after the end of the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) trolley car strike in protest over PTC’s decision to hire African American motormen and conductors. President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson to take control over the PTC under the provisions of the Smith–Connally Act and 5,000 army troops were called in to operate idle PTC vehicles and ride as guards on active vehicles until the strike ended in August 1944. Once trolley cars were phased out, Cooper continued as a bus driver for the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation

Association (formerly PTC). Rising through the ranks of SEPTA in the 1970s, Cooper was later elected as the first African American Secretary Treasurer, Vice President and President of the Transport Workers Union, Local 234, respectively. He shepherded the Local 234 membership through many tumultuous strikes as a skilled negotiator. The Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper described Cooper’s speaking style as “a riveting Sunday preacher” in public forums, “mixing sarcasm and rhetorical flair in spellbinding quantities.” It was not unusual to hear him lace his speeches with quotes from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Adam Clayton Powell, Robert Kennedy or Barbara Jordan. Off the podium, Cooper most admired and emulated the quiet, pragmatic style of civil rights icon A. Philip Randolph, whom he met and admired for years. In 1978, he married his lifelong love, the late Marion Karpeh Cooper, a divorcée whom he had courted since 1965. The two moved to Tamarac, Florida in 1984, the same year he retired as Vice President of the International Transport Workers Union of America headquartered in New York City. More than anything, Cooper loved his family and enjoyed traveling the United States and the world with his wife, from Paris to Las Vegas to his favorite Rio de Janeiro. The two relocated to Jersey City, NJ in 2007 to be closer to family when his wife became ill. He was deeply devoted to her care until her passing in 2015. Cooper ‘never met a stranger’ and engaged countless generations of people who crossed his path with charm and a ready knowledge on a variety of topics. During a trip to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2018, he had wandered off when his family found him lecturing as an ad hoc docent to tourists about the beginning of Joe DiMaggio’s career, little known facts about Negro League players and comparative statistics to today’s MLB players. For years, many marveled at his straight posture, quick gait, and disarming smile well into his final months. For his family, Cooper’s passing at 102 was too soon for a man who could still captivate a room. His children agreed, “We’ve lost our giant.”

He is survived by his first cousin George Timbers (Camille); sister-in-law Maxine Cooper; nieces Stacey Cooper-Taylor (Robert) and Michelle Cooper; stepchildren Martin Karpeh, M.D. (Julie), Enid Karpeh-Diaz, Esq. (Doris) and Marion Beckerink, Esq. (Rodney); and, grandchildren Quinn, Chelsea, Ashley, Jessica, Gabriel and Joshua. He is predeceased by his mother Nancy Cooper, wife Marion Cooper, brother Michael Cooper and nephew Donald Cooper.

A celebration of life service will be held on Sunday, June 11, 2023, 11:00 a.m. - 2:00 p.m. at Leber

Funeral Home, 2000 John F. Kennedy Blvd, Union City, NJ.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made in memory of Merrill Pittman Cooper to the

Equal Justice Initiative, 122 Commerce St., Montgomery, AL 36104 or www.support.eji.org/give

Arrangements by Leber Funeral Home.

Fond expression of sympathy may be shared at www.leber-fh.com for the Cooper family.

Show your support

Add a Memory

Share Obituary

Get Reminders

Services

SHARE OBITUARYSHARE

- GET REMINDERS

v.1.12.1