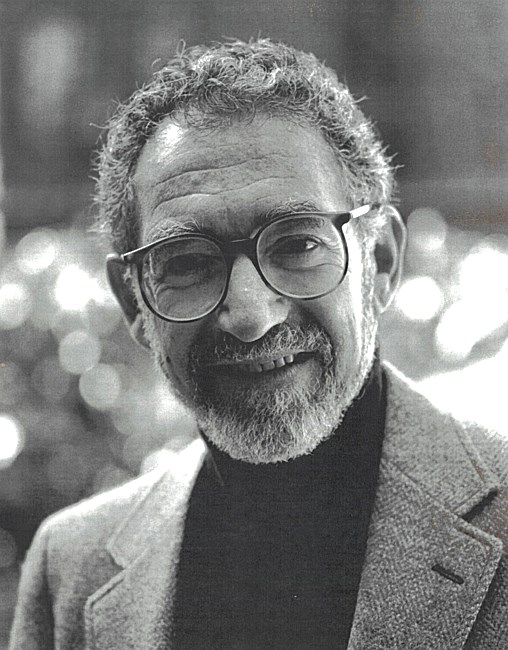

OBITUARY

Sheldon Bach

Passed away on 15 JUNE, 2021

Born in Brooklyn in 1925, he became the valedictorian of Lincoln High School. As a high school student, his photograph of the Brooklyn Bridge appeared on the cover of Popular Photography. He remained an avid and talented photographer throughout his later life. Shelly served in the infantry in WW II, beginning at the Battle of Bulge, and throughout the European theatre. Following his service, he earned a degree in comparative literature (German, Russian, French, and English) at the Sorbonne. After seven years of bohemian life in Paris, he returned to New York and was a cameraman for commercials and films until his interest in the human mind led him to enter the NYU Clinical Program for Psychology. He and his beloved wife, Phyllis, travelled all over the world, taking pictures, but he always said that there were two cities: Paris and New York.

For 58 years, Shelly practiced psychoanalysis and psychotherapy on the Upper West Side; he was a teacher and supervisor at the New York University Postdoctoral Program for Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy for over 50 years. He also trained, mentored, and supervised countless students at NYU, the Contemporary Freudian Society, and the Institute for Psychoanalytic for Training and Research (IPTAR). In 2007, he received the Heinz Hartmann Award from the New York Psychoanalytic Institute for “outstanding contributions to the theory and practice of psychoanalysis.” Shelly was ahead of his time as an analyst, deeply invested in Freudian theory, but always open to other thinkers, such as Ferenczi, Balint, and especially Winnicott. He understood narcissism, his specialty, as entailing immense vulnerability, and his narcissistic patients opened up to him in ways they could not with others. His patients felt alive in his loving mind. His prescience in his field also showed in his early interest in mind-body physiology and the role it plays in psychic processes. He was interested in alternative medicine, meditation, yoga, and humming and breathing exercises, and how such practices could help the people he treated.

Shelly was invited to share his ideas at institutes throughout the country and across the world. He authored many papers and five books: Narcissistic States and the Therapeutic Process; The Language of Perversion and the Language of Love; Getting from Here to There: Analytic Love, Analytic Process; The How-To Book for Students of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy (translated into three languages); and Chimeras and Other Writing: Selected Papers of Sheldon Bach. One reviewer commented about Chimeras that Shelly made clear “the crucial importance of the analyst’s willingness to enter into and to tolerate the experiential world of the patient over a sustained period of time in order to achieve lasting change.” He thought therapy had a great deal to do with love. He loved his patients and was deeply attentive to the nature of their suffering. He also loved his work, often remarking on how grateful he was to have found his profession. Shelly was completely open-minded and non-judgmental. He listened attentively to his patients, his family, and his friends.

Throughout his life, Shelly had an interest in gadgets. He eagerly embraced every new photographic technology, and then the advent of personal computing and cell phones. His prodigious intellectual curiosity extended to a love of learning about technologies and a love of learning on any platform. He was never intimidated by or dismissive of new ideas. He just loved to learn, especially about people’s minds and experiences.

Shelly also loved language, poetry, music, film, theater, and art. He spoke French so fluently that people in French towns always thought he was from the next town. He read widely, deeply, and voraciously: books and articles, philosophy, fiction, poems, psychology, cultural studies; and he loved a good spy novel. He could quote reams of literature by heart, including much of the Fitzgerald translation of The Odyssey. His love of language showed in his wonderful sense of humor, both dry and robust. In light conversation, he would sometimes sing a snatch of an appropriate song, usually standards and music hall tunes from the 20s and 30s. He knew so much about jazz and classical music, and he loved live music. He appreciated cinematography and great filmmaking; he and his wife loved to watch films at movie theaters and at home. Early in his career, he wrote a brilliant discussion of Bergman’s Wild Strawberries.

After every meal, Shelly would ask for dessert, preferably chocolate. He loved all kinds of food, and wine. For almost thirty years, he ate Chinese food with his best friend, Lester Schwartz, every Wednesday night; the chefs would make them spicy meals, not on the menu. At the house in the western Catskills that he and Phyllis owned for many years, he built a wine cellar full of delicious wine from across the world. He was also physically vital well into his 90s. He played street hockey as a Brooklyn kid, handball in Riverside Park as a younger man; he swam for years with Lester at the 63rd Street Y; he also learned to play tennis in his 60s and played for many years. Until 95, he got on the treadmill most mornings.

Shelly was a dear friend as well as a beloved husband, father, and grandfather. He is survived by his wife, Phyllis Beren Bach, his son and daughter, Matthew and Rebecca Bach, his son-in-law, Joseph P. Wood, and his grandchild, Jay Bach. He will be sorely missed by many, many people.

Donations in Shelly’s name may be made to Brotherhood Sister Sol https://brotherhood-sistersol.org/support/donate/

Show your support

Add a Memory

Share Obituary

Get Reminders

Services

SHARE OBITUARY

- GET REMINDERS

v.1.11.2