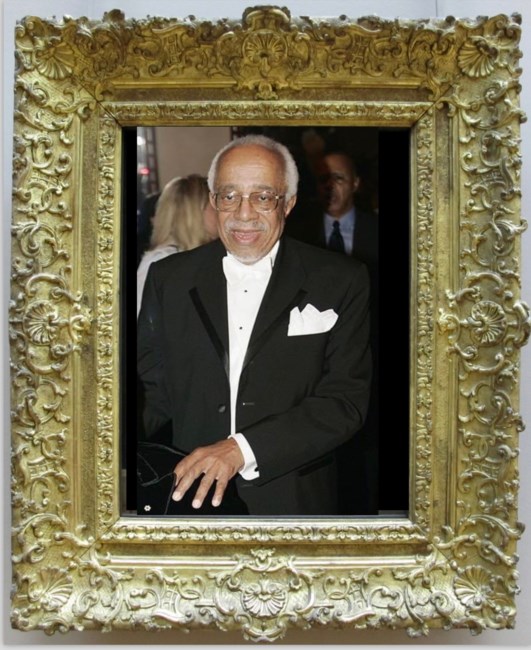

OBITUARY

Barry Doyle Harris

15 December, 1929 – 8 December, 2021

BARRY DOYLE HARRIS had, by any measure, a brilliant career as a jazz pianist, playing on over 70 records, and recording more than two dozen albums as a lead musician. However, it was his commitment to keeping the language of bebop and the spirit of its founding fathers alive that made him such an influential figure in the jazz community. Barry put the improvisations of jazz’s virtuosos under a microscope, discovering the musical grammar that makes bebop work — scales, chords, chromatic passing tones. He saw bebop as the true inheritor of the classic tradition, and jazz musicians like alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, and pianist Bud Powell as part of a tradition begun by musicians like Chopin, “the true originators of improvisation” as he called them.

Born to Bessie and Melvin Harris on December 15, 1929, the very cusp of the Depression, Barry and his brother and three sisters grew up in Detroit, Michigan in a home with few luxuries other than music. His mother often took the street car or walked to the Detroit river to catch fish for their dinner. Bessie, a church pianist, taught Barry to play the piano in the Baptist church, starting him on his life-long exploration of music and music theory. He claimed that when he attended Wayne State University he spent more time in the student union building playing the piano than attending classes. There he met Christine Brown, and they built a friendship based on their mutual love of music. They married in 1953 and had one daughter, Carol. They both joked that the reason they stayed married for almost 64 years was that from early in their marriage Barry lived mainly in New York to pursue his career in jazz!

When he wasn’t in New York or elsewhere for gigs, Barry and Christine’s small flat in Detroit would be crammed with musicians rehearsing and jamming, including his friends Euman ‘Brock’ Brockston and Jimmy Robinson. Charles MacPherson and Lonnie Hillyer prepared for their upcoming albums there. Throughout his career, he not only played with the big names in jazz, such as the Jones brothers (Hank, Thad and Elvin), Yusef Lateef, Milt Jackson, Kenny Burrell, Tommy Flanagan and dozens of others, but was sought out by them for jam sessions and informal lessons, even back when he was a young man living with his mother. Those who studied with him included trumpeter Donald Byrd, bassists Paul Chambers and Doug Watkins, trombonist Curtis Fuller, and saxophonists Pepper Adams, Charles McPherson and Joe Henderson, and when John Coltrane was performing in Detroit, he would stop by to see what new angle Harris was exploring.

Barry’s first recording was in the 1950s and over the next several decades he played on albums with Sonny Stitt, Frank Rosolino, Thad Jones, Hank Mobley, Art Farmer, Cannonball Adderley, Lee Morgan, Dexter Gordon, and Coleman Hawkins. In 1954, he replaced Tommy Flanagan as the house band at the Blue Bird Inn — playing alongside Pepper Adams and Elvin Jones and backing stars like Miles Davis and Wardell Gray, Roy Eldridge, Lee Konitz and Lester Young. He even sat in with Charlie Parker a few times and toured with drummer Max Roach and alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley with whom he left Detroit for New York.

After a few decades in New York, his close friend Pannonica de Koenigswarter, known as the Jazz Baroness, insisted that he and Thelonius Monk move into the Jazz House in Weehawken. He always acknowledged that without such a wonderful patron, he never would have been able to do all that he was able to do, especially his teaching.

In fact, teaching was a central part of Barry’s career, even after moving to New York. To keep jazz alive, Barry gave up many opportunities for fame and fortune so that he could devote himself to making his teaching accessible. He co-founded the Jazz Cultural Theater, where he offered weekly workshops – and he would never turn a student away, even if they could not afford the bargain 10- 15 dollars fee. He defined a theory of jazz piano and improvisation revolving around chord structures and improvisational choices made in split-second intervals. Perhaps a deeper lesson that Barry sought to impart was the idea that being a true jazz musician comes out of a deep, abiding commitment to the music, heightened by the joy and surprise found in an unexpected chord or rhythmic twist.

Barry not only performed, but taught all around the world, including Rome, Madrid, Paris, Toronto, Tokyo and even Buenos Aires, spreading the gospel of bebop. He held an annual residency at the Royal Conservatory in Amsterdam, alongside Frans Elsen, drawing scores of students to sessions that lasted from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. He believed that the true musician should never stop learning and studying, and continued to take lessons himself, studying with classical pianists Joseph Prostakoff and Sophia Rosoff until she died in 2017. Barry continued to do weekly in person workshops until 2019, and when the pandemic hit, he switched to teaching via Zoom right from his own piano at home, with attendance sometimes reaching more than 200. He was amazed that he could reach his global following of students from the comfort of his own home, joking how for years he had travelled the world to teach them, and now they could come to him. He taught his last class via Zoom to over 100 students worldwide, only two weeks before his death.

It was not only his peers and his students who grew to appreciate Barry’s brilliance and contributions over his seven-decade career. He received two Honorary Doctorates (Northwestern and Rutgers), and was recognized by the White House and by President Clinton for his dedication and commitment to the pursuit of artistic excellence in jazz performance and education. He was also a NEA Jazz Master, and recipient of the Grammy’s President’s Merit Award for Lifetime Achievement Award in Jazz, which he received alongside Oscar Peterson and Hank Jones. He had many other awards, too many to mention.

Yet throughout all this work and recognition, he would always return to Detroit to be with his family. He was pre-deceased by his brother, Richard Harris III, with whom he had a very close relationship, and sisters Katherine Williams, a seamstress for Motown who created dresses for the Supremes, Betty Palmer and Mayme Harris, as well as his wife Christine. He is survived by 13 nieces and nephews, 35 great nieces and nephews, 47 great great nieces and nephews, and 25 great great great nieces and nephews, a total of 120. Most importantly, he is survived by his daughter Carol and her husband Keith Geyer. Barry, just like wife Christine, loved life and definitely wanted to stay with us as long as possible, both were so strong willed that it was only because God came to get them, that they are no longer with us.

Barry was very loved and adored for his wonderful talent and his compositions, and the fact that he loved to share that talent with others to the end of his life. Because of his contributions, he is rightfully known as one of the greatest Jazz pianists and teachers of our time. His loss is felt not only by his family but by the entire music community, his students, and his devoted fans.

The visitation will be available online to the public at www.BebopHQ.com

Show your support

Add a Memory

Share Obituary

Get Reminders

Services

SHARE OBITUARYSHARE

- GET REMINDERS

v.1.18.0